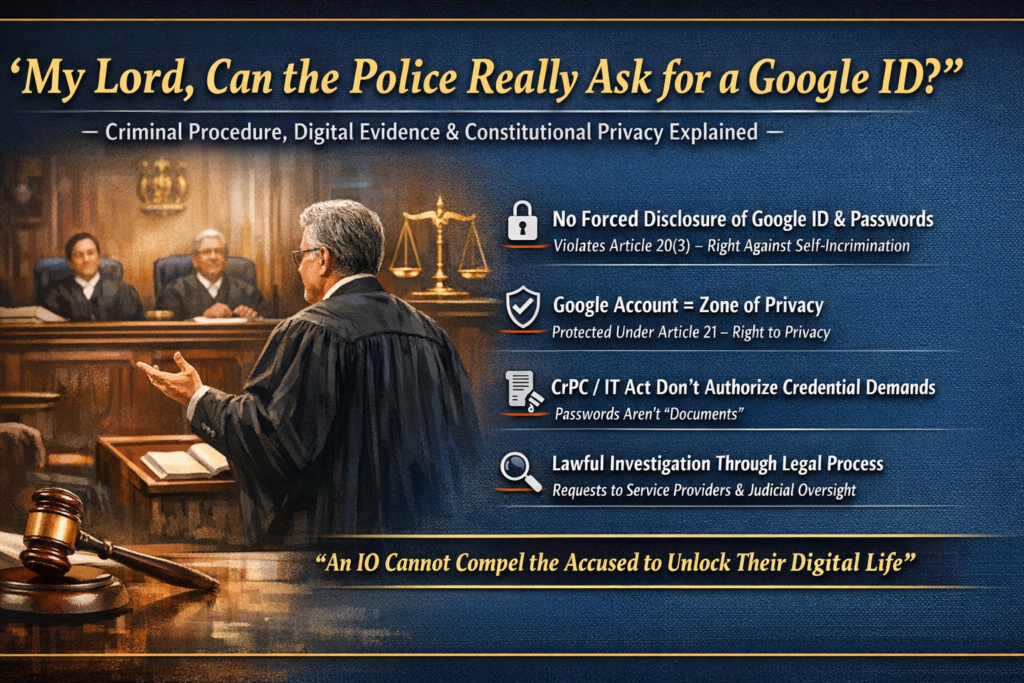

I was watching a courtroom argument on YouTube — the kind that instantly grabs your attention — where a Senior Supreme Court Advocate rose to object to a seemingly routine demand made by the Investigating Officer (IO).

The IO had asked the accused to hand over his Google ID.

For a brief moment, something unusual happened.

The Bench paused.

The judges exchanged glances. There was visible uncertainty — can an IO really ask for this? After all, we live in a digital age. Phones, emails, cloud data — everything is evidence now. Or is it?

With calm authority, the senior advocate dismantled the demand — not emotionally, not rhetorically — but legally. What followed was a masterclass in how criminal procedure, constitutional rights, and digital privacy intersect in modern investigations.

This blog captures that exact legal reasoning — the one that made even the courtroom pause.

1. Can an Investigating Officer demand an accused’s Google ID or login credentials?

Short answer: No — not directly.

An Investigating Officer cannot lawfully compel an accused to disclose:

- Google ID

- Password

- OTP

- Recovery codes

- Authentication credentials

merely by asking, directing, or informally insisting.

Such a demand cuts straight through constitutional protections and lacks statutory backing unless routed through specific legal processes — and even then, credentials themselves are almost never demandable from the accused.

2. Why this demand fails in law

Courts don’t view this as a technical issue. They treat it as a constitutional violation.

(A) Article 20(3): Right against self-incrimination

Article 20(3) of the Constitution declares:

“No person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself.”

Compelling an accused to disclose login credentials is not neutral cooperation — it is active participation in building the prosecution’s case.

Courts have consistently held:

- Passwords and credentials are testimonial

- They rely on mental knowledge

- They cannot be equated with physical evidence

This is fundamentally different from:

- Fingerprints

- DNA

- Voice samples

which are physical, non-testimonial evidence.

(B) Article 21 and the Right to Privacy (Puttaswamy)

In Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017), the Supreme Court recognised that digital life is private life.

A Google account is not just an email inbox. It contains:

- Emails

- Location history

- Search behaviour

- Cloud documents

- Photos

- Contacts

Forcing access to such data without due process strikes at the core zone of privacy protected under Article 21.

(C) CrPC / BNSS does not authorise forced disclosure of passwords

Sections 91 CrPC / 94 BNSS allow the IO to summon documents or things.

But the courts draw a clear line:

- Passwords are not documents

- Credentials are knowledge, not “things”

- An accused cannot be compelled to produce self-incriminatory material under these provisions

(D) The IT Act, 2000 offers no such power

Contrary to popular belief, no provision of the IT Act empowers police or cyber cells to force an accused to disclose:

- Account passwords

- Login credentials

- Recovery information

3. A critical distinction courts insist upon

| Person | Can credentials be demanded? |

|---|---|

| Accused | ❌ No |

| Witness / third party | ⚠️ Only documents, not passwords |

| Service provider (Google) | ✅ Yes, via lawful process |

This distinction is non-negotiable in constitutional criminal law.

4. Then how should an IO investigate Google account data?

The law does not cripple investigations — it channels them correctly.

5. Constitutionally valid alternatives available to the IO

(A) Direct legal request to Google

Using Section 91 CrPC / 94 BNSS read with the IT Act, the IO can approach:

- Google India

- Google LLC

Google may lawfully share:

- Subscriber details

- IP logs

- Login timestamps

- Device identifiers

⚠️ Passwords are never shared — under any jurisdiction.

(B) Section 92 CrPC / 95 BNSS

Used for:

- IP address mapping

- Telecom records

- Location correlation

Often combined with intermediary data to establish timelines.

(C) Search and seizure of devices

Under Section 102 CrPC / 106 BNSS, the IO may seize devices and send them for forensic analysis.

However:

- Forced unlocking is legally contentious

- Courts increasingly insist on judicial oversight

- Proportionality and minimal intrusion are key

(D) Judicially supervised access

In sensitive cases, courts permit:

- Targeted data access

- Through Google’s Law Enforcement Request System

This satisfies:

- Due process

- Privacy safeguards

- Constitutional proportionality

(E) Consent-based access — with caution

If the accused voluntarily consents, in writing, without coercion, access may be allowed.

But courts scrutinise such consent closely.

Any hint of pressure renders it invalid.

6. What if the IO threatens arrest for non-disclosure?

That crosses a dangerous line.

Such conduct may amount to:

- Illegal coercion

- Violation of Article 20(3)

- Abuse of investigative powers

Legal remedies include:

- Approaching senior police officers

- Moving the Magistrate

- Writ jurisdiction in serious cases

- Exclusion of illegally obtained evidence

7. Where the law stands today

Courts are crystal clear on these principles:

- Passwords are testimonial, not physical evidence

- An accused cannot be forced to unlock their digital life

- Investigation must go through intermediaries

- Privacy and due process trump investigative shortcuts

8. The courtroom-ready conclusion

“The Investigating Officer has no authority in law to compel the accused to disclose personal digital credentials such as Google ID or passwords, as the same violates Articles 20(3) and 21 of the Constitution; lawful investigation must proceed through intermediary-based data requests and judicially supervised mechanisms.”

That YouTube courtroom moment wasn’t just an argument.

It was a reminder — that constitutional law does not log out just because the crime is digital.

About the Author:

Advocate Sanjeev Rajput is a Ahmedabad based litigator and writer who reflects on courtroom experiences, legal advocacy, and the evolving practice of law. Through his writing, he aims to bridge the emotional and intellectual journey of litigation.